A few days after getting home, I dreamed that I flew back to Bristol Bay to fish an extra week. That’s a first, but I have had a recurring early-season nightmare where the season’s over before it’s started. This year, I had the season’s over dream on June 9th, almost two weeks before we put the boat in the water. Some of my deckhands have chalked this up to Stockholm Syndrome, where hostages become emotionally attached to their captors. Maybe. But I go back to the Bay every season because I love it, not because I absolutely have to. And I’m realizing that’s what someone with Stockholm Syndrome would say.

Or maybe it’s like the settlers captured by natives on the American Frontier, cited by Sebastian Junger in Tribe. After having been part of the tribe for some time, they were rescued and taken back to European American society, only to escape again, preferring the native way of life. Despite the back and brain-breaking 20-hour days on the boat, there’s something we prefer about that way of life too.

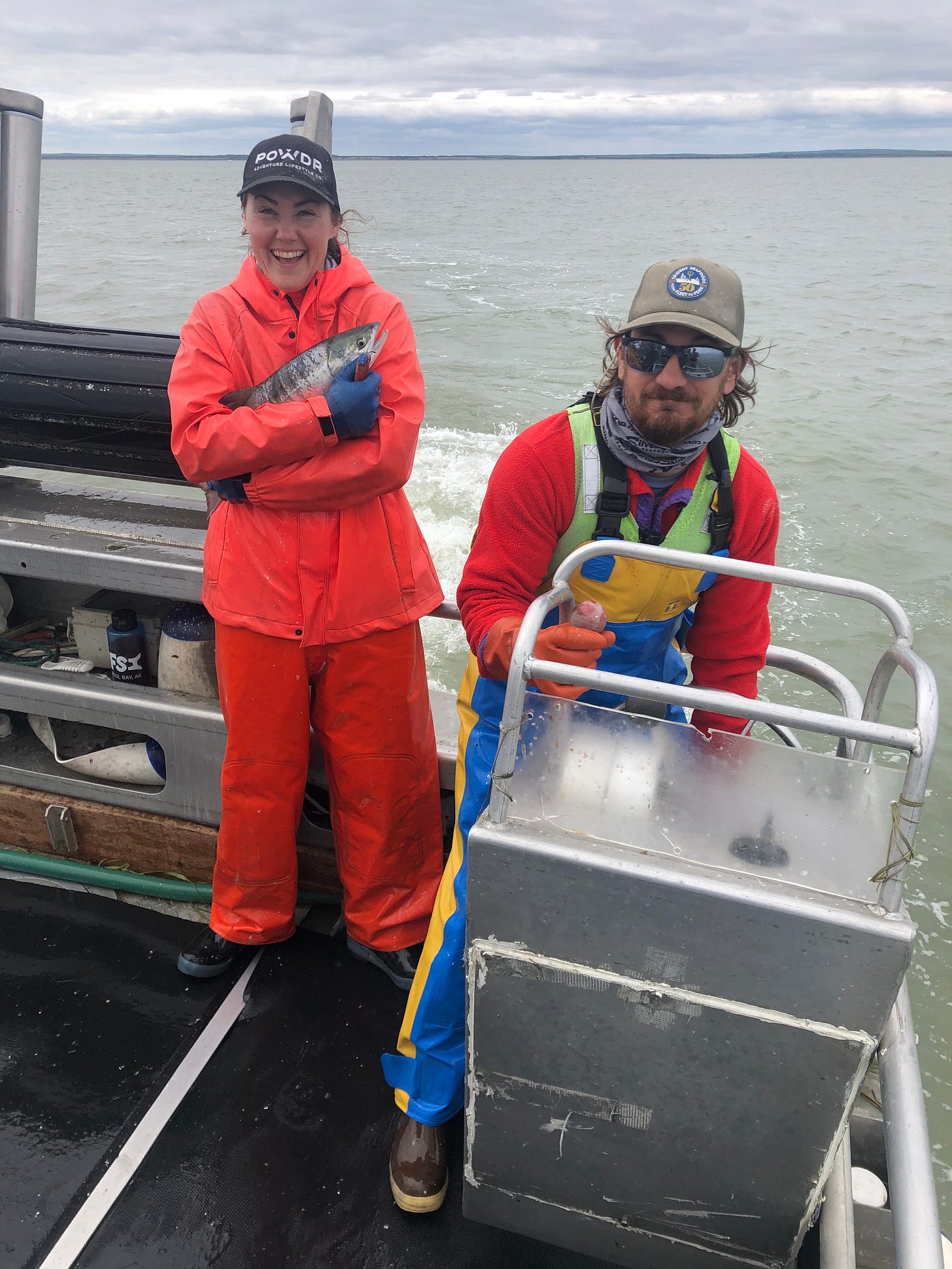

Mariah escaped to the Bay for three weeks this year, thanks to getting full-time daycare for 3-year-old Tephra and 5-year-old Levi, combined with my parents’ willingness to watch them the rest of the time. Last season, we didn’t have any childcare besides my parents, and two weeks about maxed them out. Those two weeks only lined up with the early peak, but this season Mariah made it out for the peak until the end of the season. She has more experience working on our boat than the rest of our crew, so she helps the crew find a rhythm, even our deckhands with experience on other boats.

But, as it’s been said that hunter-gatherer societies were enslaved in a way by the land, Mariah also mentioned the feeling of being a slave to the tide and wind, and the boat. She and I have talked about how I feel less trapped on the boat as a skipper than I did as a deckhand. I figured this was because I grew up and grew to love fishing in Bristol Bay more than any recreation. And since I’m constantly learning more about the boat mechanically, it seems like an ever-expanding universe, rather than a 32-foot jail cell as it had in a few of my seasons as a deckhand.

Mariah doesn’t agree that fully explains the mental divide between skipper and crew. She points out that I get to choose where the boat goes. The Bay is also a constantly expanding universe for me, as I learn how and when to make different sets. As a deckhand, it can help to be somewhat aware of where we’re fishing, to know how long until we pick the net before drifting over the line, or how long of a run it will be to the tender. But besides spotting jumpers, deckhands don’t decide where the boat goes, where we fish or unload or anchor. That lack of control, Mariah says, is the root of the cooped-up feeling, not so much the size or the comfort of the quarters. That makes sense to me, so promised to let her drive more. Or at least tell me where to set.

This also might be why Jesse, one of our other deckhands, took the helm and took us up to full throttle without warning. He came from skippering his own boat, but his boat insurance went up and his crew fell through, so he decided last minute to fish with us instead. Since he has a permit also, that meant we could fish an extra 50 fathoms of net. But when I said maybe he could give me some ideas about where to set, he said, “You only get me from the neck down.” He’s an opinionated guy though, and he could only control his impulses for so long.

We heard about a deckhand on a boat in the Nush that had an out-of-body experience after 72 hours without sleep, and Mariah observed how even at a more sustainable pace, fishing is an out-of-body experience to a degree. For an experienced deckhand, reactions become mainly automatic. Picking fish, mending net, managing the towline, swapping ends of the net, all these tasks can be done “from the neck down.” As fish come over the roller, a good fish picker instantly knows the best angle to grab them, clear them, and pick them. With experience, we get to intuit more and choose less. Even driving the boat, I’ve noticed that not having autopilot, I become the autopilot, spinning the suicide knob without much thought and somehow leaving a straight track on the GPS. The amount of time going with our guts might be part of the allure of going back to commercial fishing every year.

Plus, Mariah pointed out how many of the bigger more conscious choices are also mostly made for us, skipper included, while living on the fishing boat. The biologists say where we can fish with boundaries mapped on our GPS, when we can fish based on a combination of how many fish are in the area and, in the Naknek/Kvichak district, when the flood tide reaches a stage of 7 feet.

The tides also determine the smart places to fish, so we won’t get pushed by the currents across those boundary lines or too close to set netters. The hammering of helicopter blades just above the masthead reminds me to double-check my distance to the line too, as my heartbeat hammers to match.

The wind shifts the smart places back and forth, depending on which way it will push us and the fish, and it feeds the waves. Near a shoreline that the wind is blowing away from, the waves might be smaller because there’s less fetch, but the fish also tend to move with the wind, so they may be stacked up on the far shore where the waves are biggest and steepest as they enter the shallow water. The line between fishable and foolish is a mix of what I can see out the window, and what the glowing screens of the GPS and depth sounder tell me.

With experience, I’m taking more of this in subconsciously, freeing up my conscious mind to consider new fishing factors. I hope to eventually feel as natural in the tophouse as I do picking, knowing at a glance the best set to make. But after six seasons running the boat, I know I still have a lot to learn.

Near the end of the season, our total poundage wasn’t where I’d hoped it would be, especially with Jesse having brought a second permit on board this season. Getting new fuel tanks built and installed over the winter had cost more than I’d guessed it would, but fishing was still good enough to pay for it with an extra week on the water. The boat continued to run smoothly, and it seemed like a waste to put it up on blocks when I had another month until my other work obligations. The weather forecast was fair. I still enjoyed being on the water. We talked about moving our plane tickets back.

The crew, however, was not running smoothly. Our greenhorn had improved astonishingly little over the course of the season. The other deckhand tended to slam stuff around, which led to Mariah getting her thumb smashed under the stern roller. When I first saw it, it looked so mangled that I thought it must be broken. My mind flashed through whether we would have to leave good fishing to run her upriver to the clinic, or to a tender, and if she would have to fly out early to get to the hospital in Anchorage. She took the max dosage of ibuprofen and acetaminophen and was still beginning to black out from the pain. But with eyes shut tight and through clenched jaw, she said, “Just keep fishing, don’t worry about me.”

So I went out on deck and helped pick, while Mariah watched our drift from the tophouse. Unloading, I helped hook up brailers and she wrote down the weights. Her thumb no longer looked broken, and she could cope with the pain, but she would at least lose a thumbnail. And there was a sharp line of burst blood vessels all the way around her thumb, where the stern roller had tried to shear it off like a 200-lb dull guillotine.

She had to go home soon anyway to start a new job, and relieve my parents of our kids. So while soon it wouldn’t matter whether or not she could pick fish, I imagined she would also have trouble picking up kids or buckling them into car seats. Plus I missed my kids. I’d been away from them for seven weeks. Jesse had a baby at home too. All these factors combined to give me that end-of-season feeling, where people get hurt and things break and I don’t want to push my luck.

We might not be quitting while we were ahead, financially, but at least quitting while we were even. And physically, well, we’d survived.

But, as my dream pointed out, part of me, a less conscious and maybe less logical part of me, still wanted to be there. I would have been happy to stay an extra week or two if we’d been able to figure out a way to bring our kids on the boat, and if Mariah hadn’t gotten hurt. And if we weren’t so tired of repeating ourselves to the greenhorn, and worried about the other deckhand slamming stuff around. Big ifs.

And even in my dream, I went back and wasn’t sure if I was catching enough fish to cover the extra plane tickets. I went back though. Because awake, when I think back to the season, I don’t think about poundage caught or the greenhorn or Mariah’s mangled thumb. I think about skippering the boat towards open water, feeling out the wind and tide, and setting the net on a hopeful whim.

If you enjoyed this, please share it. Subscribe to get future posts, including my journal of the season.